The Carrotfinger Man

An Altearth Tale

by E.L. Skip Knox

(this story first appeared at Aphelion Magazine, April 2017)

Mani looked back one more time. Between the beech trees he could just make out the road as a line of brown in the distance. He looked down at the slim dirt path beneath his boots, then turned around to face his partner, Ki.

Who grinned back at him.

“I tell you, Mani, this is the way. We’ll save hours, I’m sure of it.”

This was small comfort. Ki was a good smith, but he was the kind of dwarf who was always sure, right up until he was sorry.

Mani’s beard twitched as he clenched his jaw. His back was aching again; he adjusted his pack higher onto his shoulders. The pack carried blades for Count Evrard, and human blades were wretchedly heavy. But soon to be filled with silver, he told himself, provided we get to the castle by sundown.

That was the contract, and dwarf contracts were unbreakable. Bound by stone.

They were already late. The road would take too long.

“Let’s get going, then,” Mani said.

“Right,” Ki said and set off briskly.

Mani followed after. He could not help but notice that he was stepping from sunlight into shadow.

At least the path ran fairly straight. The beech trees drew closer together. Their curved branches arched and intertwined, obscuring the sun, creating chambers and hallways below. Countless years of rotting leaves covered the ground. To Mani, it seemed as if he moved through strange caverns of wood, deep beneath the earth.

The path kept getting covered by leaves, appearing and disappearing beneath the damp carpet, but Ki trotted along in high spirits, talking of how this contract was going to save their business.

“Two short swords, two long knives,” Ki said, “and then there’s your ax. Wait till the Count sees that!”

A small fighting ax, ordinary enough. But Mani had the craft of enchanting. He also had a clever idea, and a fine ruby in his shop. The ruby infusion had worked, and now the ax cut with fire as well as with its keen edge. That blade alone could make their fortune.

Gradually, Ki ran out of babble. Mani relished the silence for a time, then began to worry about it.

Like any dwarf, Mani had sharp ears. He could hear the difference in the tone of struck metal, could sort out words from echoes, and tell the direction of footsteps in a maze of tunnels, but now he heard only the breath and footfall of two dwarves. He listened for a long time.

No birds, he thought, no rustle of a fox, no chirp from squirrels. There should be a thousand squirrels.

He was so caught up listening, he nearly ran into Ki.

“Why did you stop?”

“Lost the path.”

Mani looked down and his heart skipped two beats. All he could see were dead leaves.

“Where’s the path?”

“That’s what I was saying.”

“Ki, that’s not funny.” Mani felt his throat grow tight. “We need to go back.”

“Can’t,” Ki said. He kicked at the leaves. “I lost the path some way back, and now I don’t know which direction to go.”

Mani looked around. Deep pools of shadow lay under the massive trees. The air hung as still as velvet drapery. Light reached the forest floor in pale, golden fingers. All around him lay the damp brown leaves, trackless as desert.

A scream sliced the stillness. High-pitched, wavering, then trailed off.

“What was that?” Ki said, his voice low.

It sounded again. A woman’s voice, without a doubt, and now Mani made out the word.

“Help!”

The two dwarves looked at one another. The cry came from Mani’s left, tugging at him. He could not just walk away, pretending he had not heard, but what good could he do? He was no warrior, he was a bladesmith. What help could he give?

“Help!”

Mani loosened the long knife at his hip.

Ki’s eyes widened. “Don’t do it, Mani.”

“Ki … I ….” He found nothing to say. He gripped the knife and sprinted toward the sound.

Fool, fool, fool. Mani scolded himself, the word striking with each footfall. Fool to have left the road and fool again to have left Ki. He glanced left and right as he ran, marking his passage, as if he could find his way back again, knowing it was futile. He would be lost, was already lost. As lost as the contract would be. He would spend the rest of his days casting charms on horse shoes.

Fool.

Again the woman screamed, a thin, sharp sound.

He ran hard, struggling under the weight of his pack. At least he had not been fool enough to leave it behind.

The ground became rough, as if the tree roots only waited for someone to go astray. More than once he thought he should stop, but the cry for help sounded again, and he ran on.

Ahead the trees thinned enough for a thicket of buckthorn to erupt in a tangled arc on one side of a small clearing.

There he skidded to a halt. The bushes were impenetrable. He looked left and right. If she were dragged in here by captors or some beast, there would be signs.

Footsteps approached from behind. He whirled, knife at the ready, but it was only Ki.

“Where?”

“I don’t know,” Mani said. “She stopped yelling. You look there, I’ll look here.”

The two dashed along the length of the bushes, calling out, “we’re here, where are you?” but only silence replied. They returned to the center.

Ki looked pale. “Do you think she’s …?”

“I don’t know,” Mani said. “I could swear she was right here, but there’s no signs. Strange.”

A noise from behind caused them both to spin around.

Ki cursed and stumbled backward as if shoved. Advancing upon them was a grotesque man, dwarf-high, wearing a heavy cloak that sagged too large for his frame. A large hood enveloped his head, hiding the face. Or else, Mani shuddered, he has no face at all. The man uttered weird shrieks that set Mani’s teeth on edge.

The sleeves of the cloak hung nearly to the ground. From them emerged a tangle of green and orange, trailing on the ground like a mass of tentacles.

“Stay back!” Mani shouted, but his voice quavered.

The man came on, unsteadily. Mani raised his blade to strike. A motion at his side and there was Ki, knife also at the ready.

“Partners to the end,” Ki said, low and quick. Mani nodded and planted his feet.

The creature in the cloak uttered a different sort of shriek and stopped, teetering madly.

Then it fell apart.

The cloak opened and out tumbled two pixies, who fell to the ground yipping with laughter. They sounded like cats trying to bark.

Relief flooded over his panic, then exploded into fury. Mani raised his knife high and charged, shouting.

“Wretches! Scoundrels!”

The pixies, still entangled in the cloak, scrambled out, piping incomprehensibly. Mani tried to grab one, but it slipped from his grasp like quicksilver.

“I’ll kill you both!” Ki shouted.

“Aiee!” cried the other pixie, “don’t chop me up!”

A voice from behind them said, “Prank!”

Mani turned around. A third pixie emerged from the bushes, the thorns scarcely touching him.

“Grant mercy, sir!”

Mani stopped. Ki, knife in hand, looked back and forth between the one pixie and the two others near the cloak.

“Pixies.” Ki spat the word.

“Prank! Prank! Grant mercy, sir, it is but a prank!”

The other two took up the plea, repeating it like a formula. Their voices were high-pitched, like the cry of robins.

Ki brandished his knife.

“No, no,” cried one of the pixies, “we have called prank. Grant mercy sir, by dwarf honor.”

Ki took a step, but Mani stopped him.

“Come here, you,” Mani demanded of the two pixies. They came nearer in hesitant steps, each pushing the other forward. Over their nut brown skin they wore green linen shirts and breeches, striped in white. With yellow caps on their round heads, they looked a bit like two dandelions.

“Prank, sir. Grant mercy.” The pixies both stretched out their hands, palms up, then brought their fingertips to their chest, a motion they repeated as they spoke.

Nearby lay the cloak, its size more suited to a human. Scattered at the sleeves lay two piles of carrots. He felt ashamed that so simple a decoration should have made him think of tentacles.

Pixies, he thought in disgust.

“What do you mean by this nonsense?” he demanded.

“Grant mercy, good dwarf,” a pixie said. “It is the Carrotfinger Man we mimic. A little scare, a little fun. We did not dream to provoke.”

“What’s a Carrotfinger Man?” Ki asked. He seemed to have recovered a little.

The other pixie edged round until they were all three together.

“You do not know?”

The three spoke together in whispers. Mani caught “foreigners” and “only dwarves,” but when he overheard, “perhaps they’re simple,” he exploded.

“Enough!”

The pixies fell silent.

A snicker from Ki distracted him. At Mani’s glare, he held up two fingers close together.

“You have to admit it’s at least a little funny.” His voice was thick with suppressed laughter.

“I suppose you think being lost is even funnier,” Mani said with a snarl.

“Lost?” said one of the pixies.

“You have lost your way?”

“No, damn it,” Mani said, gesturing at the forest, “you lost it for us.”

“We cannot lose it. It was your way, not ours.”

Mani took a deep breath. Arguing with pixies required a clear head.

“I am Mani. This is Ki.”

The pixies looked identical, not only in their attire but in height, build, faces, right down to their copper-coin eyes and long brown hair. The only distinguishing feature was in the ribbons which each had worked into his hair: scarlet and black and silver, but one favored silver while the other two preferred black.

The pixies bowed. From left to right they replied.

“I am Tun,” said the silver-ribbon pixie.

“I am Udo.” He had perhaps an extra black ribbon.

“I am Eth.” The third one continued, “we are brown pixies.”

“Then why are you wearing green?” Ki asked with a smirk.

“Ki,” Mani said severely. His partner was not taking this seriously enough.

“Sorry.”

Mani kept his attention on the pixies. “We are lost,” he said, “but you are going to help us.”

“We ourselves? But we do not know your way.”

“We only know our way.”

“And the other way, but you don’t want that way.”

“We want our way,” Mani said. “You made us lose it, with your prank. We have suffered loss.”

“Loss of way.”

“A very sad day.”

“To lose one’s way.”

Mani spoke as solemnly as he could. “You are obliged,” he said.

This statement caused the pixies to put their heads together. They talked in long, soft trills, sounding like a trio of curlews. Ki started to speak but Mani waved him quiet.

The pixies arranged themselves into a line. Together they bowed low, arms wide, hands waving elaborately.

“Don’t chop us up.”

“We are obliged.”

“Don’t chop us up.”

The three looked so silly he had to chase a smile from his face.

“You must lead us out of the forest,” he insisted. “We are lost.”

“Lost is no good. Not in this forest.”

“Not in here, you see.”

“Lost is quite the wrong thing to be.”

“So it is agreed,” Mani said, trying to be patient. “You will take us where we want to go.”

“No.”

“Which is to say, no.”

“We do not know where you want to go.”

Ki said, “We go to the castle of Count Evrard.”

“We cannot go there.”

“Humans there.”

“Humans do not like pixies.”

In unison the three of them said, “Particularly brown pixies.”

Ki took a half-step forward, which made the three pixies take two steps back.

“Listen,” Ki said, and all three pixies leaned forward, hands cupped to ears. “Get us to the edge of the forest, where we can see the castle. I know it’s near. I could see this forest from the castle walls when I was there.”

“He was at the castle.”

“He has a mighty sword.”

“He is a great warrior.”

Mani said, “Do you all three have to speak? Can’t you let one speak for all?”

In unison the pixies said, “No.”

“There are two ways to go.”

“The one way, and the other way.”

“You don’t want to go the other way.”

Mani made a show of putting away his knife. “Take us the one way. To the edge of the forest where we can see the castle of Count Evrard. You are obliged.”

The pixies bowed again, then spoke.

“We agree.”

“We are obliged.”

“We agree we are obliged.”

Ki whispered at Mani’s ear. “Do you trust them?”

“I trust they will try,” Mani said. “It’s not like we have a choice. Do you think you can find our way out?”

“No,” Ki said meekly.

“So we trust them.”

The pixies chirruped.

“Follow us.”

“Do not stray.”

“Do not go the other way.”

The three pixies set off at a brisk pace. There was no path to be seen, but they trotted along without hesitation, their soft boots scarcely disturbing the forest floor. Mani and Ki followed a few paces behind.

“I hope they can get us out of this forest,” Mani said.

“There is time yet,” Ki said, “I’m sure of it.”

“I still can’t believe I ran off like that.”

“I can. You went to rescue a fair maiden,” Ki said with no hint of irony. “Truly, it was brave.”

“Truly, it was stupid,” Mani said.

“You worry too much.”

“And you don’t worry enough.”

They walked in silence for a while. Mani berated himself, listing all the bad choices he had made, beginning with taking this contract in the first place. Only when the pixies stopped abruptly did he emerge from the review of his misfortunes.

Udo and Eth were arguing with Tun—the one with the extra silver ribbons stood with arms folded, shaking his head, while the other two trilled angrily at him.

“Now what?” Mani groaned.

“Everything all right?” Ki called.

The pixie voices pitched upward, then Udo—he of the extra black ribbon—said, “All is well, all is good.”

“We continue, good and well,” Eth said.

The silver-ribbon pixie shrugged and pointed, and the three set off again, yellow caps bobbing.

Ki followed them, calling back, “When it’s the only way, it’s the best way.”

Ki and his sayings. Mani trudged after.

After an hour or so, a path appeared. The leaves were still heavy, but they drew back to lay bare a track that was never more than a foot wide. Sometimes it shrank to mere inches, with leaves piled deep as if someone had come along dragging a branch, but it never completely disappeared.

“Those stupid pixies found it,” Mani whispered to himself.

“First the little path,” Eth said, “then the big path, then out.”

“Obligation done,” said Tun.

“Then we have fun,” sang Udo.

Eth trilled at them and they shushed each other. Mani could not help smiling. If they got him out of the forest, let them jabber.

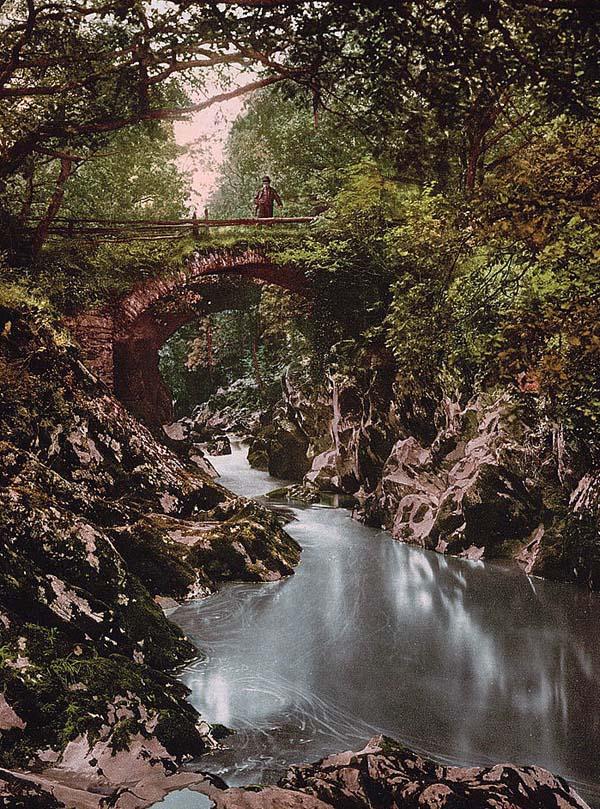

The path came to a stone bridge that arched over a ravine. Paving stones at the foot of the bridge hinted at a road, but it had long been blanketed by leaves.

Two trees stood like sentries on either side of the roadway. Near the ravine, the forest gave way to a border of dogwood and fern, then at the edge, dark, bare clay with a few yellowish vines trailing over the side. The smell of foul water fingered up from below.

The bridge vaulted in a half-circle high over the ravine, climbing steeply as if to avoid being touched by anything below. Moss covered much of the surface, mud and leaves covered the rest.

It did not feel to Mani like they had got to much of anywhere. Beech trees overhung the road, their branches intertwined. Golden light filtered through. He squinted. Was it from the west? Could the hour be so late?

High voices broke into his thoughts.

“What’s going on?” Mani demanded.

Eth stepped forward. “No troubles,” he said.

“We have come the other way,” Tun said.

Mani blinked. “What? How?”

“It is a mistake,” Tun said gravely.

“The forest plays tricks,” Udo said.

“No troubles,” Eth said, “we make it right. No troubles.”

Ki leaned over to Mani and whispered, “I don’t much like this.” Then, to the pixies, he said aloud, “Is this the right way or not?”

“We go that way,” Eth said, pointing to the bridge.

“Yes,” Udo said.

“No,” from Tun.

“It is unanimous,” said Eth.

“It can’t be unanimous,” Ki said. “That one said no.”

“It is unanimous,” Eth said, “with we two.”

Tun muttered something.

“Here we go!” Eth declared.

“Wait,” Mani said, “what did he say?”

“Unimportant.” The pixie smiled and tilted his head.

“I’ll decide that. What did he say?”

“He said, ‘Carrotfinger Man,’ but not important.”

“What are you up to now? You said that Carrot … thing … was a trick,” Mani said.

“No trick,” Tun said, “you go that way, the Carrotfinger Man gets you.”

“No troubles,” Eth said. “The Carrotfinger Man used to live near here. He ate many pixies, but he was killed by an elf chevalier, long ago.”

“Very dead,” agreed Udo.

“Yet there are stories,” said Tun.

“Long ago?” Mani asked. For pixies that could be anywhere from weeks to centuries.

“Long ago,” said Eth, spreading his arms wide for illustration.

“The Carrotfinger Man ate my grandfather’s uncle,” Tun said.

“Your grandfather’s uncle got drunk and wandered off,” Udo said.

This set off another round of chirps and trills among the pixies. Tun shoved Udo and in a flash the three were circling each other, shrieking like gulls.

“Stop,” Mani said sternly. “I’m not going to stand for this.”

They stopped. Tun folded his arms over his chest. “Then sit,” he said, “but Carrotfinger Man is real.”

“Carrots for fingers?” Ki muttered. “Doesn’t sound dangerous.”

“No, it doesn’t,” Mani agreed.

Tun placed one hand over his heart and raised the other above his head. He spoke as if to an assembled crowd.

“The Carrotfinger Man lies in wait in the dark places of the world. He grabs when you are not looking. He snatches when you are not thinking. He takes you into his den and drains you dry and chews you up and no one finds you and your families weep.”

The pixie lowered his hands. “So it is said.”

Ki looked at the bridge, craning his neck. He smiled weakly. “That was quite a speech,” he said.

“Killed by an elf, you say?” Mani said to Eth, who nodded.

“Long ago.”

Mani and Ki looked at each other. Mani shrugged. Ki frowned.

“We follow the pixies,” Mani said. “They led us this far safe enough.”

“Gah,” Ki said, “they’re the reason we are this far.”

Mani slowly and deliberately drew out his knife.

The pixies backed away, whispering, “chop chop.”

“We will follow you, but no tricks,” Mani said. “I’ll be keeping this at the ready.”

“Wise,” said Tun.

“We will go over the bridge, to show safe,” Udo said, scowling at Tun.

“All is well,” Eth said, and the three set off.

They climbed the steep bridge, looking left and right. They paused for a moment at the top, then went down the other side, keeping step with each other. The arc of the bridge hid them.

Mani waited, straining to hear. Ki looked at him and manufactured a wan smile. Mani listened to the silence of the forest. After a few moments, the pixies reappeared at the top of the bridge.

“We crossed,” Eth called out, waving them on. “All safe.”

The moment he said this, something thin and ropy swung out from beneath the bridge. Dark green like a vine, it had an elbow and a hand. Impossibly long fingers whipped around Udo, who screamed once, then arm and pixie disappeared over the side.

Eth still had his hand in the air. Tun was already running and shouting, but it was in pixish, so all Mani heard was a cascade of noise. Eth sprinted after him.

“Help, help!” Eth gasped. “It’s him. He got Udo.”

“We know. We saw,” Mani said, “but what…?”

A terrible squeal came from the ravine, cut off by a deep-voiced thump, like a hollow tree trunk being struck.

Tun spun around and sprang away without a word. Eth called out after him, but the other did not slow. In a moment he was gone into the ravine.

“What’s he think he’s going to do?” Mani asked.

“Help,” Eth said. He looked pointedly at Mani’s knife.

“What, me? With this?” Mani laid the knife in his palm, to show how small a weapon it was.

“Mighty warrior,” Eth declared.

“I’m no warrior. I’m just a bladesmith.” Mani’s heart raced. He swallowed hard.

“Help,” Eth said, more firmly. He darted in, snatched the knife from Mani’s hand, wielded it.

“Warrior,” Eth declared, then dashed away.

“Hey, my knife!” Mani shouted, but it was no use. In two breaths, Eth had disappeared after Tun.

“Ki, did you see that? Crazy pixie … wait, what are you doing?”

Ki had loosened his pack and set it on the ground.

“We have to help them,” Ki said. Mani looked at him, surprised at the resolve in his tone.

“Help them? They’re probably already dead.”

Ki drew one of the short swords from his pack. “No,” he said, “I can hear them.”

It was true. Desperate wren-squeaks came from somewhere below.

“We can’t,” Mani said. “We’re not warriors. Not even an elf could kill it.” His insides were turning to water.

“We have to do something,” Ki said. “We’re obliged.”

That word. The pixies had honored their obligation and now they were in trouble. Obligation cut two ways.

“All right,” Mani said. He set down his own pack and pulled out the Count’s ax. He stood up, hefting it. “Dwarf honor.”

The ravine was about ten feet deep, with steep sides. At the base a shallow stream meandered through heavy mud, muttering its way among reeds.

“Down we go,” Ki said, already going over the side.

Mani cursed desperately and followed. His feet sank two inches when they hit bottom. “Where?” Mani whispered. Ki nodded toward the bridge.

Under the bridge lay deep shadows. One of the shadows moved, turning toward them. A man-like shape stepped out into the half-light. Taller than two dwarves, its face held eyes as wide as the palms of Mani’s hands. These sat on either side of a mouth that ran vertically down its long, narrow face. It wore debris rather than clothing, its body covered with clumps of earth and twigs. Strands of green hair hung down over its narrow shoulders.

Its arms were thin, like vines, so long its hands hung at its knees. At the end of those hands were fingers even longer. Filthy with muck, but plain as anything they were orange. The fingers hung right down to its feet, where they writhed along the ground. In one of its hands it held a pixie by the neck. The creature threw it back under the bridge. It yelped once.

Ki shouted and charged, brandishing the short sword. Mani said “No” in a helpless way but could not move. Ki got no closer than a few steps away from the monster when one long arm looped around his leg and snatched him up. It held the dwarf in front of its face, regarding him. Ki flopped and twisted like a caught fish, mouth gaping. It slid its other hand over Ki’s face. One of the orange fingers ran along Ki’s eyes, two went to his ears. One hovered over his mouth, probing his lips.

That brought Mani back to himself. He shouted. The monster’s head swiveled. Its eyes contracted to pinpoints, then went big again. It swung Ki, dashing him against the side of the ravine. The dwarf tumbled like rags onto the muddy ground and lay still.

Mani sprinted, ax in hand. His vision narrowed as he ran; he saw only the ropy arm, the undulating fingers. Two more strides and he dove. The Carrotfinger Man swung a hand down, but missed.

Mani hit the ground and rolled. A stone dug into his back, but he got to his feet, his momentum carrying him into the shadows under the bridge.

The stench of rot assaulted him—rotting plants, rotting flesh. He heard the trill of pixie voices, but could not see them.

A thunderous roar shattered the air, echoing against the stone. Mani turned in time to see one of the Carrotfinger Man’s arms whip toward him. He reacted in panic, hacking at the long hand with the ax. To his surprise, he connected. The ax blade rippled with yellow fire as it sliced. The hand went flying over his head, into the shadows.

The monster shrieked, holding one arm up, grasping the wrist. From the stump oozed something viscous. The screaming mouth distended to the width of the face.

Mani darted from under the bridge, but the Carrotfinger Man leaped in pursuit. Its gait was uneven and it still gripped its own wrist. Mani had no thought to fight the thing. He wanted only to get to Ki and to get away.

The monster lashed out with its remaining hand. Mani brought the ax up to defend, but the arm snaked past. Orange tendrils as strong as roots tightened around his wrist and forearm. The long arm twitched and Mani lost his hold on the ax. He was jerked forward, landing face first in the mud. He lifted his head, gasped a single breath, then a foot rammed his head into the muck and kept it there with crushing strength.

Mud covered his mouth and nose. The creature’s foot stood across his neck, its long toes stretched over his head, digging into his scalp. Only his ears were above the muck.

He held his breath, but his heart thundered. He had to breathe soon. He tried to think: let the air out, twist around, grab fresh air. But if he did the one without the other, syrupy mud would flood into him, and that would be the end. The thought made his heart pound even harder.

He heard something that sounded like birds trilling furiously. He thought this strange. Not one bird had sung in all this forest. The thought faded like mist.

The weight lifted from his neck. Air exploded from his mouth. He twisted, and his lungs filled not with mud but with sweet air.

He rolled onto his back, coughing, then got to his knees. The air cleared his eyes and his mind. Above him, the monster was trying to knock pixies away. They clung to him, one on his back, one on each leg.

Mani could not see the ax, but nearby on the ground lay Ki’s short sword. Mani got to his feet. The pixies were fighting, shrieking like jackdaws.

Mani retrieved the sword. The shrieks shrilled upward. He looked. The monster was spinning around, madly trying to grab a pixie with its one hand, but they scurried around it like squirrels on a tree.

Mani charged. He got behind the creature and struck, hitting it just behind the knee, the blade cutting deep.

The Carrotfinger Man lurched to one side, bellowing like a bull. The pixies sprang away as it twisted violently and fell to the ground. It thrashed back and forth.

The pixies shrieked, “Cut off the head! Cut off the head!”

Mani turned to them. Each of them was cut, their clothing torn. Their eyes shone like needles.

“My ax,” Mani said.

All three turned as one and pointed.

“Guard Ki,” Mani ordered, then ran to the ax. He wiped the mud from it, then ran back. Its blade was glowing like a torch.

The creature lay face down. Mani leaped onto the creature’s back and swung. The ax bit into the neck. Fire erupted, but the blade passed through smoothly. The head rolled away. The body shuddered and lay still. It did not bleed, but a kind of dark, orange mud oozed from the neck. Mani stood atop it, gasping and trembling.

A strange popping sound made him look down. The fingers on the remaining hand one by one shot away from the hand, each landing several feet away.

Mani jumped away from the body. Strength fled from him and he sat down hard. The ax viper-hissed against the mud. His mind galloped and reeled like a panicked horse. His blood cried out for action, but there was suddenly nothing to do.

A weak trill made him turn his head. Udo and Tun were bent over Eth, uttering long, soft coos. Udo looked up.

“He is hurt,” he said, “but he lives.”

Mani hurried to Ki’s side. Blood covered one side of his head, but he was breathing.

“Ki.”

Ki’s eyes fluttered.

“Mani,” he whispered. He managed to sit up, leaning against the side of the ravine.

“You’re hurt,” Mani said. Ki wiped at his face. A long gash ran along his forehead, but it was not deep.

“You’ll be all right now,” Mani told him.

“That thing?”

“Dead.”

“You sure?”

Mani managed a weak smile. “I’m sure.”

It was an hour before they left, for the pixies declared the fingers must be destroyed. Ki was still dizzy, so Mani indulged them.

The three pixies scoured the ravine for the orange tendrils. Each time they found one, they fell into a frenzy of smashing with stones until the thing was obliterated.

At the end of it there was some discussion as to whether they had found nine or ten, with accusations all around about not knowing how to count. The dwarves put an end to the dispute, insisting they needed to get going and reminding the pixies they were still obliged.

The five had to go some way before they could climb back out of the ravine, after which the pixies again led the way. They were solemn, speaking rarely, in quiet tones. Half an hour later, they came out from under the trees. Meadows crept to the forest’s edge, and farmland lay beyond. Atop a distant rise stood a square, stern castle. Mani turned to the pixies, who now stood in a line, caps in hand.

“You have found our way,” Mani said, “but more than that, you saved my life. Thank you.”

“You saved us,” Eth declared.

“Then we saved you,” Udo said.

“Saved together,” Tun said.

Ki smiled at them. “And together we killed the monster, which no one else could do.”

Tun looked uncomfortable. “Nine,” he said.

“Ten,” Eth insisted.

“I counted ten,” Udo said firmly.

“So be it then,” Tun said, but he looked unhappy.

“Nevertheless,” Mani said, determined to be cheerful, “now you can go home. The obligation is done.”

“We won’t go back,” Tun said.

“Never go back,” Udo said.

“We will find another home,” Eth said.

“Where will you go?” asked Mani.

“We do not know,” Udo said.

“Not there,” Eth said.

Tun merely nodded.

The pixies and dwarves parted ways. The sun had just touched the western horizon.

By the following April, the enterprise of Mani & Ki was known throughout Bretagne, as famed among humans as among dwarves. They had taken on a journeyman and two apprentices, for Count Evrard himself kept them busy with many new orders.

The three brown pixies ought to have been famous, for they had a grand tale to tell, and they told it often. Fame did not come to them, however, for who believes a pixie?

At the very end of April, near the arched bridge that stands just inside the forest, a vagabond happened upon a carrot of unusual size growing in the bank near the stream. Being hungry, he pulled and tugged until the thing came free. It was absurdly large and curiously smooth, but he had not eaten in two days, so he took an eager bite.

And spat it out again.

The texture was wrong, the smell was bad, the taste worse, and no carrot should ooze when bitten. In disgust, the vagabond hurled the thing high and far, and went off in search of real food.

The object landed atop the bridge. Slim tendrils probed the stones, but found no nourishment. April left, May arrived, and the orange fingerling turned to ash under a bright spring sun.

The End