Back to Part 1

Arles

Arles

The gardiens of the Camargue helped Talysse and Detta escape their pursuers, under the cover of bringing bulls to the arena in Arles, the capital city of the Kingdom of Arelat.

The real city of Arles is a Roman foundation, which is why there’s an amphitheater here. I swiped the Latin name, Arelat, and then just swapped the two words: Arelat becomes the name of the kingdom while Arles is the name of the town. This was a real kingdom, formed out of the detritus of the old Carolingian Empire. It survived in one form or another, sometimes also being called the Kingdom of Burgundy, into the 14th century.

Bullfighting can be found all around the western end of the Mediterranean, but here in the Camargue (a form can be found in Andalusia as well) the practice takes a non-lethal form–none of the bulls are killed. Here, the raseteurs compete to snatch little ribbons that are tied to the bull’s horns. The event is timed. If the bull succeeds in warding off the raseteurs, he wins and can now be put out to stud for a high price. Those who lose may try again another year. It’s colorful and exciting, perfectly in the spirit of southern France (there are videos of the contest).

I decided to combine that event with a tournament, which is the point at which Talysse and Detta are joined by Jehan d’Ursay, the elf chevalier. All in all, Arles served as a nice turning point in the story.

I decided to combine that event with a tournament, which is the point at which Talysse and Detta are joined by Jehan d’Ursay, the elf chevalier. All in all, Arles served as a nice turning point in the story.

The Wagoneers

How could I differentiate these from Romani (often called gypsies)? The elves of Altearth are a scattered people, with significant differences between each type. I hit rather late on the idea that there would be one type of elf who did not live in a forest or a fishing village or under a hill, but would travel about. Why would they travel? I did not want these elves to be exiles, though in any sedentary society those who move about are innately suspect and it is no different with the wagoneers. This kind of elf had a social function: they carried messages between elf communities.

This choice had some interesting consequences that don’t really come up much in the book. To be reliable as messengers, they needed to show up with some regularity. This meant they travel a kind of route, with a schedule that at least follows the seasons. Recalling the medieval pied poudre (medieval merchants; literally, dusty-foot), the wagoneers go to specific water places–sea or lake–with some regularity. Maybe annually, maybe more or less often. This is the ritual of “washing the wheels.” They carry the messages memorized, to keep them private, which means my elves have unusually good memories. I also gave them an archaic, formalized language used for these messages and for little else.

This choice had some interesting consequences that don’t really come up much in the book. To be reliable as messengers, they needed to show up with some regularity. This meant they travel a kind of route, with a schedule that at least follows the seasons. Recalling the medieval pied poudre (medieval merchants; literally, dusty-foot), the wagoneers go to specific water places–sea or lake–with some regularity. Maybe annually, maybe more or less often. This is the ritual of “washing the wheels.” They carry the messages memorized, to keep them private, which means my elves have unusually good memories. I also gave them an archaic, formalized language used for these messages and for little else.

Each wagon is its own unit. Each may go with a karwan (from the Persian for caravan), but may choose to join another at any time. I suppose there would be some process for forming a new karwan, but I’ve not worked that out. I should also mention that the name Cierzo Karwan is not arbitrary. Cierzo is the name of one of the thirty-two directional winds; more familiar names would include sirocco and mistral. And that caused me to suppose there are thirty-two karwans in Altearth, but I’m not sure I’ll hold to that.

One last bit of wordplay involves routiers, which I use as a synonym for wagoneers. It’s still a modern French word, meaning truck driver. In the Middle Ages, though, it had quite a different meaning. During the Hundred Years War, mercenaries were widely employed by both the French and the English. At times, peace would break out and the mercenaries found themselves suddenly unemployed. Especially here in southern France, where royal power was weak, bands of mercenaries roamed the roads (the routes), stealing and extorting to support themselves until war should return. Some even took over castles and became more or less independent powers. I chose to go with the modern connotation, of those who travel the roads; the medieval connotation was too strong for me to use it exclusively, so I invented the term wagoneer.

Into the Mountains

Our heroes pass near the town of Béziers, a town with a certain medieval infamy. The whole region through which the story passes was once the stronghold of the Cathars, famous heretics (who had a most curious and fascinating set of beliefs). Theirs is a long and tragic story that began in the 12th century and did not end until well into the 14th century. It includes a fierce war, sometimes called the Albigensian Crusade (after the town of Albi). At Béziers there was a terrible sack of the city, and great slaughter of Cathars and Catholics alike as the soldiers ran unchecked through the streets. It was later claimed that Arnaud Amalric, the spiritual commander of the troops (he was an abbot) deliberately ordered the massacre, saying “Kill them all for God will know his own.” The attribution comes from two decades later; it’s impossible to know if Amalric actually said this. It is a quote from 2 Timothy, ch. 2 v.19, which has mutated into a rather ugly slogan, in sharp contrast with a very beautiful town.

Our heroes pass near the town of Béziers, a town with a certain medieval infamy. The whole region through which the story passes was once the stronghold of the Cathars, famous heretics (who had a most curious and fascinating set of beliefs). Theirs is a long and tragic story that began in the 12th century and did not end until well into the 14th century. It includes a fierce war, sometimes called the Albigensian Crusade (after the town of Albi). At Béziers there was a terrible sack of the city, and great slaughter of Cathars and Catholics alike as the soldiers ran unchecked through the streets. It was later claimed that Arnaud Amalric, the spiritual commander of the troops (he was an abbot) deliberately ordered the massacre, saying “Kill them all for God will know his own.” The attribution comes from two decades later; it’s impossible to know if Amalric actually said this. It is a quote from 2 Timothy, ch. 2 v.19, which has mutated into a rather ugly slogan, in sharp contrast with a very beautiful town.

Carcassonne

Just as our heroes never entered Béziers, so they did not quite make it into Carcassonne either. This town is much photographed. Its famous walls were not yet built at the time of this story (which takes place in the early 20th century AUC, or the late 12th century in Earth chronology), so it was really nothing more than a town of regional importance. Talysse would not have seen what is pictured here.

Just as our heroes never entered Béziers, so they did not quite make it into Carcassonne either. This town is much photographed. Its famous walls were not yet built at the time of this story (which takes place in the early 20th century AUC, or the late 12th century in Earth chronology), so it was really nothing more than a town of regional importance. Talysse would not have seen what is pictured here.

Except for the river. That is the Aude, running swift and deep as it makes a big curve around Carcassonne. It is the river crossed by the wagoneers during a storm, the one in which Talysse rescues Brasc’s horse.

The Pyrenees

The Latin word is Pirinaeus. I try to use the older words where I can and where they seem to fit. These are the mountains that divide modern France from modern Spain. In the Middle Ages the line was much less clear. The Kingdom of Navarre often straddled both sides of the mountains at the western end. At the eastern end, any number of powers great and small held sway, including Perpignan, Catalonia, Aragon, Narbonne, and Foix. Basques are normally associated with Spain, but there are quite a number of Basques living on the northern side of the Pyrenees. And, of course, over near the Atlantic Ocean lies the famous pass of Roncevaux (Roncevalles), where the Song of Roland’s final scenes are set. That legend provided the key element for A Child of Great Promise–the staff of the Archmage Turpin.

The Latin word is Pirinaeus. I try to use the older words where I can and where they seem to fit. These are the mountains that divide modern France from modern Spain. In the Middle Ages the line was much less clear. The Kingdom of Navarre often straddled both sides of the mountains at the western end. At the eastern end, any number of powers great and small held sway, including Perpignan, Catalonia, Aragon, Narbonne, and Foix. Basques are normally associated with Spain, but there are quite a number of Basques living on the northern side of the Pyrenees. And, of course, over near the Atlantic Ocean lies the famous pass of Roncevaux (Roncevalles), where the Song of Roland’s final scenes are set. That legend provided the key element for A Child of Great Promise–the staff of the Archmage Turpin.

Also historically real is the village of Puig Balabor (Puyvalador) I tweaked the setting a little bit, but it really does lie next to a lake. The whole business of a rendezvous is not European at all, as far as I’ve been able to discover. It belongs to the American West. Since that’s where I live, I figured it would only be appropriate to include something of that background into the story. It gave me the excuse to bring together elves, dwarves, and humans.

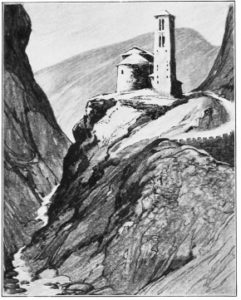

The two forts shown here were part of the inspiration for the Redoubt. The tower is actually in the Pyrenees, while the other is in the Cevennes region, called Villefranche.

Conclusion

A Child of Great Promise forced me to flesh out more of the backstory of elves. The reader may have noticed that I rework the convention of wood elves, dark elves and other D&D types into fisher elves, hunter elves, and wagoneers. There may be other types as well. I like the idea of using occupation or activity as the defining characteristic, rather than using place or color.

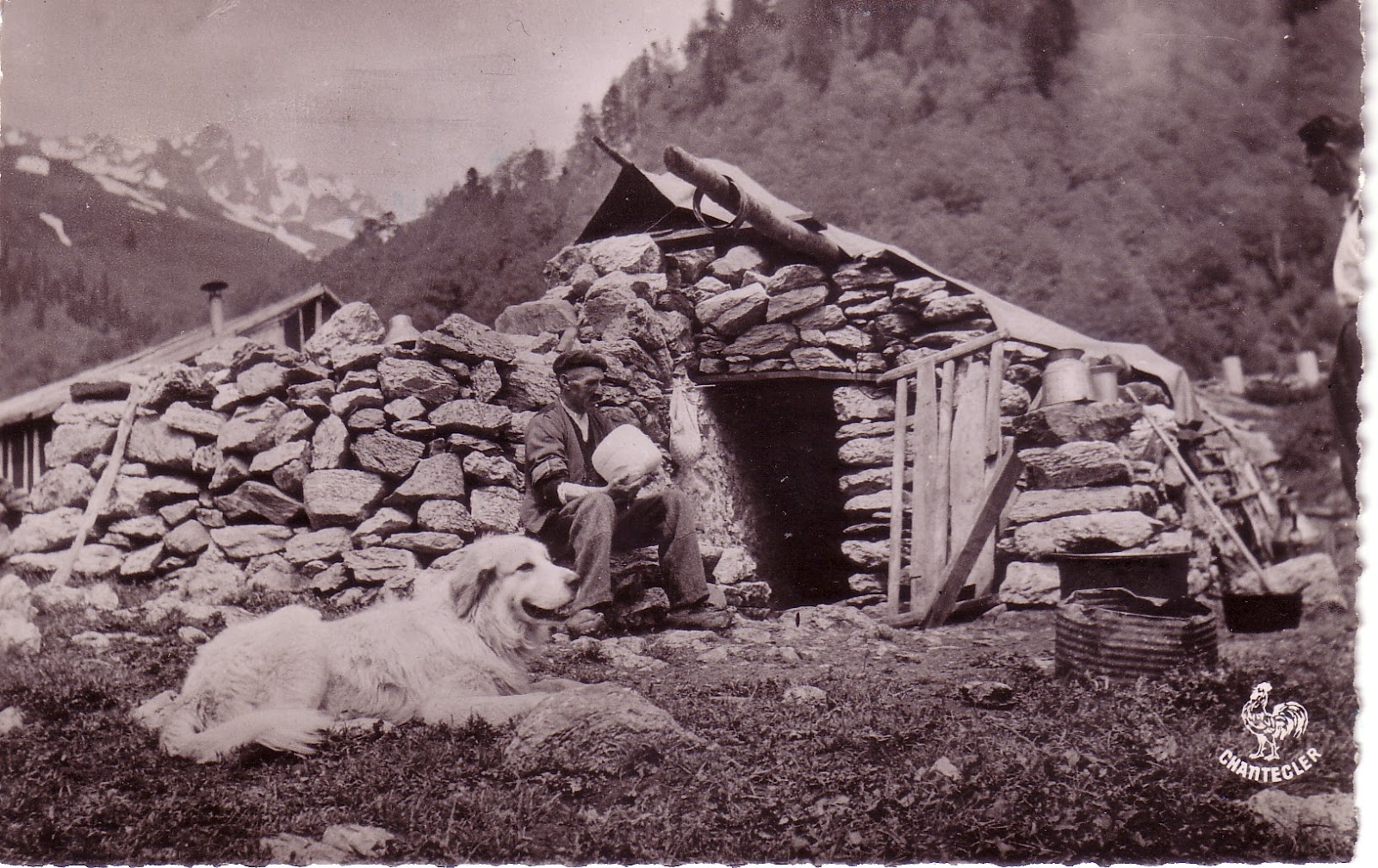

I’ll close with a picture that I found early during my research. I never quite found a place to use this Pyrenean shepherd or his dog in the story, which is a pity. The Great Pyrenees dog is as magnificent as the better-known Saint Bernard. And I love the rugged simplicity and utter isolation of the shepherd’s hut. Perhaps they’ll find their way into another Altearth tale.