Hannibal at the Rhône

A bit of Roman history

Most people have heard about Hannibal, and if they’ve heard anything about him it’s that he crossed the Alps with elephants. Which he did. In October of 218 BC.

But that’s not the most remarkable aspect of Hannibal’s march, at least not to me. The more remarkable achievement is that he crossed the Rhône River earlier that same year. With elephants. With an enemy waiting for him on the other shore.

That the enemy waiting for him wasn’t comprised of Roman legions is another remarkable accomplishment by this remarkable general. Hannibal began his invasion of Italy over in Spain, and Rome expected to stop him there. After all, in Spain were major cities held by Rome, plus the Ebro River, plus the Pyrenees Mountains. All that should have slowed Hannibal even if they did not stop him outright. Rome sent armies to Spain to make sure Hannibal never got out of the Iberian Peninsula. Meanwhile, Rome sent armies into Africa, to strike at the Carthaginian homelands.

It was an excellent plan, which Hannibal promptly tore to shreds. He knocked out the Roman cities, slipped past the Roman legions, over the Ebro and across the Pyrenees.

OK, Plan B. Stop Hannibal in Gaul (southern France). Rome had made allies among the Gallic tribes, and she would send Roman legions to defend the Rhône River line. There was no way for the wily Carthaginian to get past that!

It would take time for the Roman legions to get to Gaul, though. New soldiers had to be raised and shipped to Massilia (Marseilles), for Rome had already committed troops to Spain and Africa, where Hannibal no longer was. So she depended on those Gallic tribes to delay him until the Roman troops could arrive.

So it was that Hannibal rolled up to the Rhône River in September 218 with about 46,000 men and 37 elephants. On the east side of the river were the Volcae, the local tribe, with perhaps a comparable number of men.

The river at this point was a half-mile wide, maybe even wider (as much as a thousand yards). This meant crossing in boats, and the Volcae had taken most of those from the western shore. Some of Hannibal’s men could swim, but that’s a long way to swim only to land on banks held by the enemy. Only a madman would make such an assault.

Or Hannibal.

As he had his men seize what boats they could find, others began fashioning canoes. Meanwhile, he sent Hanno, one of his commanders, with a few thousand men northward, to find another crossing.

Because Hannibal had a plan.

Hanno found a crossing twenty-five miles north, which was not a ford but at least had an island to provide cover and a resting point. Many crossed in boats, but some swam, inflating bags under their shields to carry equipment. They landed uncontested on the east side, rested, then moved south.

Hannibal had arranged for a signal. When Hanno was in position, he was to send up smoke. Hannibal, meanwhile, had used the time not only to build a crossing fleet, he did so openly, keeping the attention of the Volcae on him. They had no idea Hanno was on their flank.

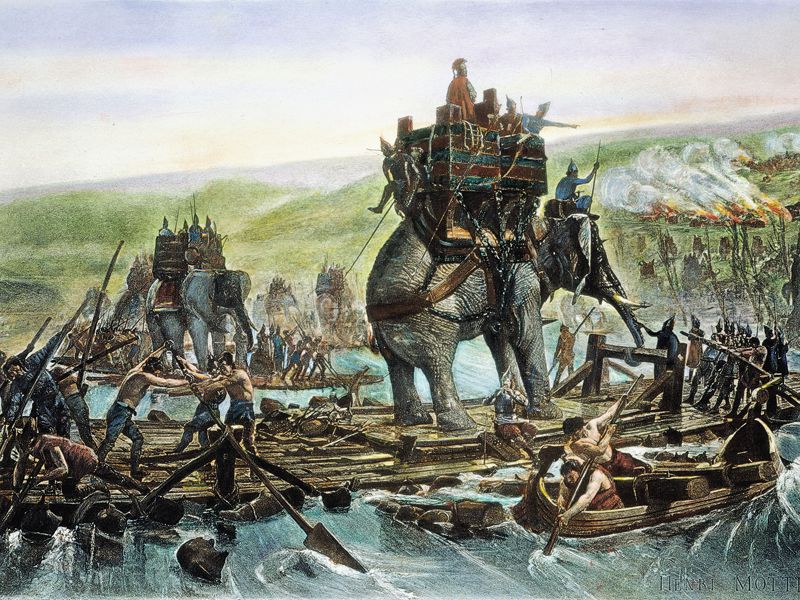

At the signal, Hannibal attacked. Because it was Hannibal, it was an exceptionally clever attack. He chose to attack across a bend in the river, setting forward a line of heavier boats that served to moderate the current. The main part of his forces crossed downstream on smaller craft.

The Volcae gathered to throw back the Carthaginians, but Hannibal—who was in one of the lead boats—managed to gain a foothold on shore. At that moment, Hanno attacked in two prongs. One group took the Volcaean camp and set it on fire, while the other fell on the rear forces. Assaulted now on three fronts, the Volcae panicked and thought only of fighting their way out from this terrible foe.

The battle was pure Hannibal: careful planning, a thorough knowledge of the enemy and the terrain, and a boldly decisive blow. When the Romans landed at Massilia a few days later, they found their enemy was already on his way to the Alps. They never touched him or even saw him until he showed up in Italy a month later.

What about the elephants, you ask?

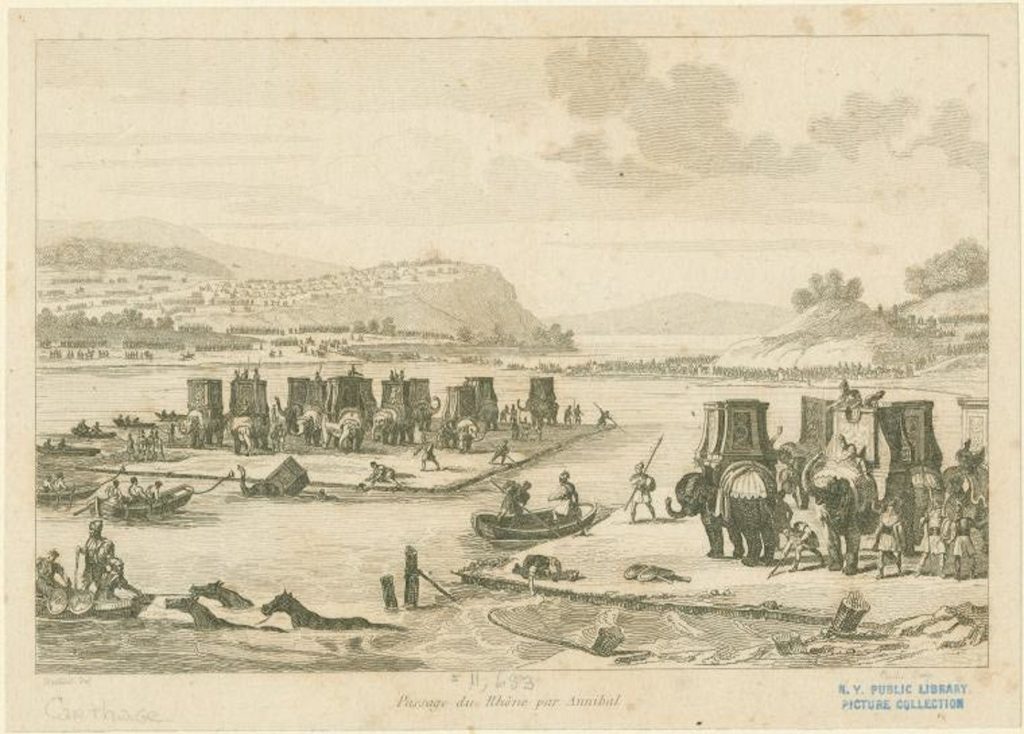

They crossed two days after the battle. On rafts.

Not just any rafts, but enormous constructions twenty-five feet and twenty-five wide. He ordered a chain of rafts tied together stretching out into the river. These were unmoving and were covered with dirt to make it look like land. The lead female elephant was brought out and the other elephants followed her.

The final raft in the chain was the only true vessel. Once an elephant was on it with its handlers, the raft was cast loose and towed across to the other side. A few elephants did panic and went into the river, but they swam and all made it across.

So, by the time Hannibal’s elephants arrived at the Alps, they had already not only fought in battles, they had crossed a mountain range (the Pyrenees) and a river nearly a half-mile wide.

Hannibal must be counted not only as one of the great generals of history, but one of the masters of logistics as well.

Oh yeah, and he managed to storm around Italy for the next fourteen years before Rome finally managed to drive him out.

You can read more about Hannibal online or in any of several books about the man and his times. One source, written by yours truly, is here

http://europeanmiddleages.info/westciv/punicwar/

which covers all three of the Punic Wars.